Back in the early 1990s, the corporate world was seized by a concept called “business process re-engineering (BPR),” the goal of which was to rethink business from the ground up, questioning every assumption, and redesigning processes from scratch to achieve massive gains in efficiency and competitiveness.

BPR spawned conferences, books, and countless consulting engagements, but there’s little evidence that anyone benefited from it other than the authors and consultants. It’s not that BPR was a bad idea; rather, few organizations are capable of the kind of massive change it demanded.

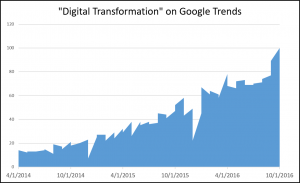

This year’s version of BPR is “digital transformation,” and the chart to the right pretty much tells the story. A Google search on that phrase turns up 7 million results, and the term has become a staple of press releases and corporate collateral. Is digital transformation destined to change business as we know it or will it wind up on the scrapheap with BPR?

This year’s version of BPR is “digital transformation,” and the chart to the right pretty much tells the story. A Google search on that phrase turns up 7 million results, and the term has become a staple of press releases and corporate collateral. Is digital transformation destined to change business as we know it or will it wind up on the scrapheap with BPR?

Unfortunately, the latter is more likely. Interest in digital transformation has been spurred by the success of a few disruptive companies and egged on by technology vendors eager to find a way to sell more gear. But scroll down that list of Google search results and you’ll notice something interesting: there’s lots of talk about how to digitally transform, but very few examples of companies that have done it.

Corporate structure resists transformation change. While top executives may see opportunity, the people below them tend to see only layoffs, paycuts, retraining, and long hours with little reward. Middle-managers, whose value is often defined by the size of their budgets or staff, have no incentive to change anything. They are the tripwires of transformation.

McKinsey has estimated that the failure rate of large-scale change programs averages 70%. “For individual organizations and their leaders, disruption is episodic and sufficiently infrequent that most CEOs and top-management teams are more accomplished at running businesses in stable environments than in changing ones,” analysts Michael Bucy, Stephen Hall, and Doug Yakola wrote in a recent report.

About the only time transformative change does occur is when a business confronts its own mortality. IBM largely reinvented its business in the early 1990s, when demand for mainframes tanked, but it reduced its workforce by half in the process. Domino’s Pizza became a hub of digital innovation in its market only after its shares sank to $3 per share in 2008 and its brand was becoming a social media laughing stock.

Such examples are rare, though. More typical is the example of the newspaper industry, which was forced to transform when advertising revenues collapsed, but found that its operationally-oriented executives had neither the vision nor the willpower to make the necessary changes.

The more practical approach to transformation is incremental. Find those cells of creativity within the organization and put them to work on small projects that can yield short-term, tangible results. Build and expand on successes. The most important cultural change you need to make is to stop penalizing failure. Unfortunately, even that objective has proven difficult outside of Silicon Valley.

Former Cisco CEO John Chambers has been frequently quoted for his prediction that 40% of today’s largest companies won’t exist in 10 years. He’s probably right, but fear is only a motivator for people at the top. To get organizational buy-in, everyone has to envision an upside for them. Without hard examples of success to point to, digital transformation runs the risk of ending up as another good idea that was too big to make real.

Image via Pixabay