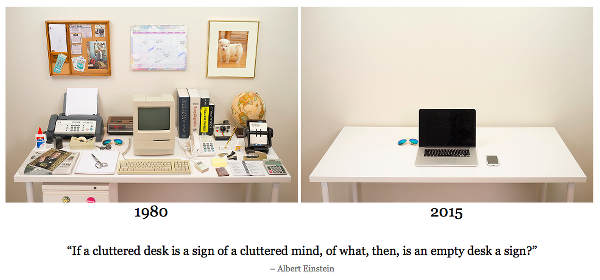

Last year, the Harvard Innovation Lab produced an interesting video showing the evolution of the desk from 1980 to 2015. That video showed the dramatic transition that happened from atoms to bits over the last 35 years or so, and many argued that, to be more precise, the desk and the laptop themselves should have disappeared at the end, with the mobile device replacing them all. One could go one step ahead and argue that the sunglasses or even digital contact lenses would eventually be the only thing left in a few years, as wearables and miniaturization go mainstream.

While that transition happened, something else was also deeply transformed, but was not as easy to visualize in a short video production. Our collective attitude towards privacy changed drastically over that period, especially in the last 10 years. While privacy is not dead – despite the 320 million results returned by Google in response to that sentence, as of this writing – it’s certainly hurt enough to fit the definition of casualty: “a person or thing badly affected by an event or situation.” And privacy, as immunization, is not something we have full individual control over: a weak link can break it in ways that are very hard to prevent. Even if you have never posted any information about you on any website, chances are that somebody else did, sometimes even a person you don’t know.

As long as a large enough number of individuals or organizations are willing to digitally give up some of their privacy – or that of their acquaintances – for the benefits of that information exchange, there will be some information about most of us available online. Those benefits range from the instant gratification of likes and comments in social networks to the usefulness of search engine results. The moment I try to search for an old friend’s name in Google or Facebook, I feed “the machine” with a crucial piece of information: that somehow I have or had some degree of relationship with that person. Furthermore, perhaps fuelled by the whole NSA surveillance debacle, an increasing number of people believe that everything, from Siri to your Samsung TV, may be spying on you – just google it and you’ll find all sorts of “evidence” for that.

This is not to say that everybody should abandon the use of technology and move to the middle of nowhere just to protect our privacy. The point of this article is not to be negative about the whole digital transformation, but to raise awareness that privacy has been severely diminished to all of us over the last decade or so, regardless of how careful we are individually with our digital activities. To some extent, that was unavoidable, and has been happening since the dawn of mankind: as humans transitioned from nomads to farmers to urban dwellers, some level of privacy was given up each step of the way, as being part of increasingly complex social contracts implies that more individual information needs to be exchanged for the framework to be functional. But in the very long term, privacy and technology tend to follow a co-evolution pattern, where mechanisms to reclaim the lost privacy become more sophisticated after each technological advancement. Privacy advocates play a crucial role in this game: privacy will not be dead as long as enough of us cherish and long for it.