When visiting IBM’s Big Data site, a reader is greeted with this bold statement: “90% of the data in the world today has been created in the last two years alone”. No matter if the right figure is 90, 80 or 70%, there is no denying that we are all drowning in data. Just take a look at your email inbox, your Facebook wall, your cable TV directory, and the volume of your digital photo or audio collection. Sometimes it’s hard to believe that the first PC I owned, 20 years ago, had a puny 40 MB hard drive. Looking at the professional side of things, the scenario is even scarier: you go away for some well deserved vacation, and on your first day back you have hundreds, if not thousands, of email messages waiting for you. To add insult to injury, you don’t even have time to process that backlog, as your calendar is now crowded with double or triple-booked time-slots. You then start feeling that you did not actually take a week off, you just compressed the work of 2 weeks in one. Is there any way out of this mess? Are we going to be perpetual prisoners of the humungous amount of data surrounding us?

The bad news is that things will get worse before they get better. Several of us are working longer hours, taking work home and shrinking our weekends. We are only half joking when we say that vacation is regular work with a nicer view. Part of the reason this is happening is that our processes and tools at work were developed at a time were work was simpler. Over the last 10 to 15 years, our jobs became more global and complex, with more technologies to master, more convoluted business processes, more governance and regulatory constraints, and more aggressive competitors. On top of that, the volumes of information we now have to process to get things done have exploded. And we are still trying to do all that using the same tools from a decade ago: meetings, phone calls and emails.

If you are a so-called “knowledge worker,” think about your day. You likely spend the vast majority of your time doing three things:

- Writing or reading documents (Word, PowerPoint, Excel, PDF) and exchanging them with your co-workers using SharePoint, Lotus Notes, network drives or email attachments

- Processing your email inbox or crafting well thought, well written email messages

- Meeting with others (face-to-face, over the phone, or using some other kind of remote technology)

Every day in the office, you create a wealth of knowledge, very valuable to you personally, your colleagues, your organization and the whole ecosystem around you. However, all that knowledge is hidden from the vast majority of people who could potentially benefit from it, as the results of your work end up disappearing into thin air, or locked in places that are not easily accessible to others, not even those with a legitimate reason to consume it. Even when digitized and made digitally available to others, most enterprise search engines are very inefficient in finding content that is relevant, current and authoritative. This illustration conveys that idea very nicely:

Extracting Knowledge, by HikingArtist (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Each one of us has an immense amount of knowledge in our heads, our inboxes, our SharePoint or Lotus Notes repositories, our local or networked drives, but the amount that is readily available to others who need it is just a drop in that ocean. In most organizations, the only way to move that knowledge from where it resides (your brain) to where it’s needed (somebody else’s brain), is via a conversation or an email exchange. There is very little re-use of that initial effort. To some extent, we are like squirrels, who spend the whole summer collecting and burying an incredible amount of food – nuts, seeds, conifer cones, fruits, fungi and green vegetation – but when it comes time to reap the benefits of that labor, they can’t find the vast majority of it. In fact, we are probably worse than squirrels: studies seem to indicate that those little rodents fail to recover about 74 percent of the nuts they bury. I would guess that we are not even that lucky in our work lives.

This is where social technologies at the workplace shine: by moving conversations and content to a social business platform, you create a digital network of people and content, creating multiple paths to find the information that you need, when you need it. Relevant and authoritative information is no longer buried like forgotten memories whose neuron pathways have been weakened by time and low usage. It’s like moving goods from a stand-alone store at the outskirts of a remote village to the main square of a burgeoning city, where life is happening and everybody can look at them.

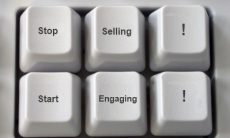

Naturally, the current commercial implementations of social platforms are still far from perfect. They won’t be a panacea to address all issues related to our inability to cope with the volumes and complexity of information around us. But they are a necessary step for us to get there. By diversifying our digital communications toolset, they better equip us to use the right instrument for the task at hand. Emails and meetings are good for peer-to-peer communications or quick back-and-forth interactions, but they are poor channels when it comes to searchability, re-use and organic dissemination of information. That’s where activity streams, “walls,” tweets, wikis, blog posts, discussion forums, social file sharing, social bookmarking and other social technologies come handy.

Rest assured of one thing: the day will still have only 24 hours for the foreseeable future, and human beings will still need to sleep, rest and have a personal life, so we will collectively find a way to handle that situation. We’ve been doing that all along: human migrations, agriculture, urbanization, the industrial revolution and the information age are our responses to somewhat similar challenges we faced in the past. Social technologies are a small, but important step in that sequence of human accomplishments.