Six years ago, NYU professor and author Clay Shirky, affirmed that “the problem is filter failure, not information overload.” The problem of having more information around than what we can possibly process has been with us since ancient times. As long as we can have good filters to separate the good from the bad, having more information is better than its alternative: not having enough information.

Many people disagreed with him, including Nathan Zeldes, who wrote a passionate piece back in 2010, entitled “Yes it IS Information Overload, Clay Shirky, not only Filter Failure”:

The problem of Information Overload as I see it, the one that’s robbing millions of people of their productivity, sanity and quality of life, is definitely new, going back to the proliferation of email in the nineties. It is not that there’s a lot of information; it is that there’s a lot more information that we are expected to read than we have time to read it in. It’s about the dissonance between that requirement and our ability to comply with it, and this requirement was not there in Alexandria or in Gutenberg’s Europe: you were free to read only what you wanted to and had time for. This is what has changed, not just the filtering. Take email: the real problem isn’t spam, which is easily dealt with; it’s the scores or hundreds of work-related messages you receive each day, and the fact that replying intelligently to even the fraction that is really important forces many to work late into the night, 7 days a week. This is an intensely real nightmare for managers, engineers, and many others.

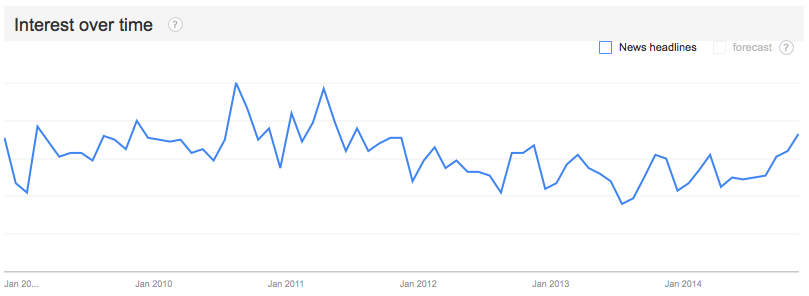

Clearly, no matter who’s right or wrong on this debate, we are all witnessing a stalemate: the problem has not gone away and no easy solution is in sight. A look at Google Trends since 2008 shows that our obsession with “information overload” goes up and down throughout the years, but it’s currently almost at the same point where it was 6 years ago:

Even though a clear solution for this issue has not emerged yet, fragments of it are maturing all over the place. Gmail’s ability to sort out the inbox into Primary, Social, and Promotions is a good start, as not all emails are the same. Flipboard and Zite showed that news curation and aggregation can be done above the level of individuals picking their own RSS feeds. Twitter showed the significance of trending topics. Social platforms often rely on social interactions such as likes and comments to determine relevance. Inbox by Google, still in Beta, is also promising and shows a glimpse of what the future may look like. All this seems to indicate that Clay Shirky was onto something when pointing out that better filters were needed to deal with the dilemma of “too much information, not enough time”. However, a complete solution to it will need to resolve two other challenges.

The first challenge is to bridge the enormous gap between those who found ways to process information faster and those who never adapted to it. In a world where everybody’s inbox and outbox fill out at the same speed, nobody cares about information overload. We are all as good or as bad as the next person. The stress comes from the uneven flow: water is coming in faster than we can take it out. To level the playing field, we must come up with communications platforms that both our kids and our grandparents can use without significant learning effort.

The second challenge is to reduce complexity by bringing the abstraction one level up. Email is just too granular, the equivalent of binary code compared to natural language. Social platforms helped a bit, but – keeping with the metaphor – they are still pretty much like the Assembly language of communications. They represent a step in the right direction, but by no means are they the final solution.

Obviously, we are not there yet, and may be still years away from finally finding something significantly better than the good old triumvirate of classic enterprise communications: meetings, phone, and email. But it’s important to note that we won’t solve the core problem of information overload by inventing solutions that are increasingly more complex to use. Whatever comes next must be focused on the same user inclusion and simplicity principles that made their predecessors so successful and long lasting.