The last 20 years have witnessed many success stories over the net: sites such as Yahoo!, Altavista, Geocities, AOL, Google, Amazon, WordPress, eBay, Hotmail, Wikipedia, MySpace, Flickr, Delicious, YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, Quora, Pinterest all had their days of glory. Some are still around, others fell into obsolescence, but each one of them changed the way users perceived and used the Internet. Vendors of enterprise software naturally followed suit and came up with a number of corporate solutions to mimic the capabilities of those popular online services. However, often the results observed inside the firewall were disappointing.

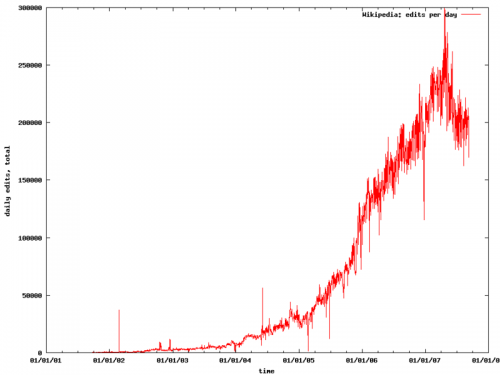

You may no longer remember this, but back in 2006, wikis were all the rage. Nature – the most cited scientific journal around – had just published an article stating that “Wikipedia comes close to Britannica in terms of the accuracy of its science entries”, and by the end of the year, the seminal book “Wikinomics: how mass collaboration changes everything”, by Don Tapscott and Anthony D. Williams was published. In the meantime, this is what happened to Wikipedia:

Wikipedia Growth – Source

At the time, many organizations started to adopt wiki solutions, ranging from the free MediaWiki engine used by Wikipedia to more enterprise-y solutions such as Atlassian’s Confluence. The idea was that, if we made our corporate pages editable by any employee, we could build a comprehensive repository of information that’s always kept up-to-date. Seven years later, very few companies, if any, have experienced sustained success using that wiki-based knowledge management strategy. Most corporate wiki sites have only one or two authors, and the vast majority of content created back then is now stale. However, Wikipedia is still very successful, as the #6 site in the world according to Alexa. Not bad for a non-profit organization.

Similar stories could be told about old-fashioned intranet websites, enterprise search, corporate blogs, microblogging and social networks. Even if you use Google as your corporate search engine, you’ll notice that the results are not as accurate or crispy as the ones you get at Google.com. Why does that happen?

It happens because, as obvious as it may sound, your corporate intranet is not the Internet. To use an analogy, the Internet is similar to a very mature tropical forest ecosystem. Millions of years of evolution since Devonian times created these self-regulated systems we call tropical forests, with thousands of species occupying very specific roles in maintaining a dynamic equilibrium. Nobody took care of them, but somehow they became fertile ground to fascinating forms of life, that almost magically tend to keep reinventing themselves through silent mutations and natural selection.

Your intranet on the other side, is much more like a garden. Some may be large like the wonderful Kew Gardens, others are small like the one in your backyard, but they all require constant care. Lots of care, to the point that you may end up feeling like you are Homer Simpson and everybody else’s intranet is Ned Flanders’ backyard. Believe me, most likely they are just as bad as yours.

There are at least five key aspects that distinguish your intranet from the big and not-so-old net:

1. Small audience sizes: the same way mature forests evolved over millions of years while the garden in your backyard is probably not even a century old, top Internet sites have millions of users but your corporate intranet count the users in the hundreds or thousands. Even if you are a “one in a million” kind of person, in Facebook there are 1,000 people just like you, and that is a crowd. The concept of a long tail is very relevant there. Thus, lots of communities centered in niche subjects can survive on the Internet, but your corporate community of, say, curling enthusiasts, may not be that successful in the long term.

2. Nature of cross-reference: PageRank works well for Google as popular or important pages are linked from all over the place in tweets, blogs, status updates and plain old websites. So it’s intuitive that pages with lots of incoming links are more relevant than pages with only a handful of them. Inside the firewall, that difference is not significant. Some very important corporate pages will have zero links pointing to them from other webpages. If enterprise search could take links from emails into consideration, the relevance of search results would be much improved, as important pages are more likely to be referred to often in emails.

3. Free Agency: the Internet is basically a bunch of free agents with a very faint association with the websites they use the most. Google quickly replaced Yahoo! as the search engine of choice once people noticed their results were more relevant or up-to-date. You may have been the most devoted user of MySpace back in 2005, but probably have switched to Facebook without any regret a few years later. On the corporate side, lack of alternatives determine your loyalty to online services: if you don’t like your expense system or Outlook or SharePoint, that’s too bad: you can’t just switch to your system of choice.

4. Anonymity: as you know, on the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog. On the other side, in your corporate social network, it’s very hard to be a dog. Most interactions are not anonymous, and even lurkers are easy to spot. If everybody else in your department are active participants in your internal community, people will soon notice your silence or your absence. The whole dynamic of participation is affected by that. While you’ll have less trolls and bullies inside the firewall, you may also have less candor in the interactions. Participation (or lack thereof) may be driven by career aspirations, fear of push backs, or plain peer pressure.

5. Operational cycles: Wikipedia and Facebook had the luxury of not being successful for several years before they became big hits. Corporations typically operate in annual cycles that need to produce results on a yearly basis. If your corporate wikis, blogs or social networks don’t show early results, they will soon be considered failed experiments and will be sent to the graveyard of good ideas proven to be useless.

This is not to say that your Intranet or internal Social Business initiatives are doomed from the get-go. On the contrary. They can be wildly successful if you understand the differences above, and stop treating your enterprise blogs as if they were WordPress, your corporate social network as if it were Facebook and your corporate wikis as if they were Wikipedia.

In my next post, I’ll elaborate on how you can use those differences to develop a much more robust social business and Intranet strategy that maximizes your chances of success. Stay tuned!