Disclaimer: This is an updated writing of a post I wrote 8 years ago for a blog that no longer exists online, but the generational theme has never been so current.

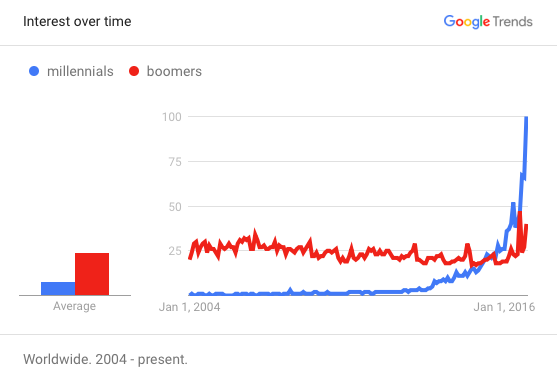

A quick comparison in Google Trends between the words “boomers” and “millennials” seems to closely reflect our obsession with the generation born after 1980:

If you’ve seen any presentations in the last decade talking about the multiple generations composing today’s workforce, chances are that you’ve already seen the following table, or one of its multiple variations, all somehow influenced by the 2002 book When Generations Collide: Who They Are. Why They Clash. How to Solve the Generational Puzzle at Work (Lancaster and Stillman):

| Traditionalist | Boomer | Gen X | Millennials | |

| Training | The hard way | Too much and I’ll leave |

Required to keep me |

Continuous and expected |

| Learning style | Classroom | Facilitated | Independent | Collaborative and networked |

| Communication style |

Top down | Guarded | Hub and spoke | Collaborative |

| Problem-solving | Hierarchical | Horizontal | Independent | Collaborative |

| Decision-making | Seeks approval | Team informed | Team includes | Team decides |

| Leadership style | Command and control |

Get out of the way | Coach | Partner |

| Feedback | No news is good news |

Once per year | Weekly / daily | On demand |

| Technology use | Uncomfortable | Unsure | Unable to work without it |

Unfathomable if not provided |

| Job changing | Unwise | Sets me back | Necessary | Part of my daily routine |

If you are wondering where you fall in this division, here are the boundaries:

- Traditionalists, born between 1900 and 1945;

- Baby Boomers, born 1946 to 1964;

- Gen-Xers, 1965-1980;

- Millennials, or NetGens, born after 1980

More recent versions of this comparison table would also include the so-called Generation Z, roughly defined as the one born in the late 1990s.

The first time I saw this table, I liked the way it summarized the generational differences, to the point I considered using it in a presentation for a client engagement. But when I proposed to add this table to the material I was developing—part of a collaboration strategy for a large government agency—I had enlightening conversations with the folks I was working with, both of them boomers and brilliant. The more vocal one said something along these lines:

I don’t buy this. When I was 18, I was very much like the millennials described in this table. The behaviors described here have a lot to do with personal traits and life cycle. Today’s millennials, once they get married, start a family and get a mortgage, may become more settled and act pretty much like a boomer. Besides, there are young folks today that are uncomfortable with change, thrive under hierarchical structures, and prefer things to be run the “conventional” way.

He actually used much stronger words in his disagreement, and that passion made me pause. It became clear to me that comparisons like the ones in that table could be perceived in a few years as being ageist, and that it would not necessarily help us to actually understand the differences between people.

Our brain likes generalizations. It helps us to create a simple model of how life works and simplifies our decision making. But generalizations are typically based on perceived averages. And in the real world, there is no such a thing as the average person, the average Asian, or the average woman. You probably have seen one of the multiple incarnations of “if the world were a village of 100 people” (see here and here for more details). The hypothetical average human being would be Asian, adult, heterosexual, Christian, an urban dweller, and make more than $2 a day. However, the vast majority of the human population does not fit that full profile, even though those are the dominant attributes in each category. For example, 48% live on less than $2 a day, and 49% live in rural areas. Those attributes are independent variables, they don’t come in bundles.

Naturally, for ease of analysis, it’s natural and useful to divide large groups of people in segments, like we saw in the US election polls, with voters divided in categories like white college-educated women and Hispanic working-class men, so that you can see trends and patterns—you obviously cannot plan a campaign customized to each of the 60 million potential voters. The danger is the opposite thinking: any assumptions made because you happen to be white, female, college-educated would be a misuse of segmentation, and we often fall in that trap.

There’s a Brazilian song that says something along the lines of “looking from a close range, nobody is normal” (“de perto ninguém é normal,” Vaca Profana, Caetano Veloso, if you need to know). That’s so true. Just imagine the table above trying to do the same with gender, race, or sexual preferences. You would probably think that to be very inappropriate or stereotypical. One of the things that make humanity fascinating is exactly how complex and different we are. Nobody is “one in a million.” There was never a person like you, and there will never be. We are all truly unique, each one of us a long tail of our own. So please don’t tell me that you are too old to blog or that you “get” technology just because you are supposed to be a NetGen. There’s nothing like living in exponential times: the only thing you are supposed to be is yourself.